In this day and age, you would have to be living under a rock to have avoided the terms “staph infection” or “MRSA.” For many, those words strike a sense of concern and even fear; but often, people do not understand what the terms mean. For many years, MRSA infection was well known and understood primarily by healthcare workers, in particular, hospital personnel. In recent years, MRSA has increased, not only in healthcare settings, but also in our communities. Staph infections are now commonplace among athletes, both competitive and recreational; therefore, we need to educate athletes regarding this serious and now rather common infection.

What is Staph?

Staphlococcus, or “staph,” is a strain of bacteria that can cause infection. There are more than 30 different types of staph bacteria, but not all cause infection. In fact, a person can be colonized with bacteria, which means that bacteria are present on the surface of the body without causing disease in that person. But if the skin is open, as with a cut or puncture, staph bacteria can enter the wound and cause an infection.

What is MRSA?

MRSA, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is but one particular staph strain, so named because of its resistance to antibiotics. MRSA is a strain of bacteria that evolves and mutates after antibiotic usage. Antibiotics, such as penicillin, cephalosporin, sulfanamide, and vancomycin, are prescribed medications given to destroy bacteria that cause infection. Anytime a bacterium becomes resistant to a particular antibiotic, a potential treatment has been eliminated and another antibiotic must be developed to combat that particular infection. Drug-resistant bacteria, such as MRSA, often exist in areas where antibiotic usage is prevalent, such as healthcare settings. Until the early 1990s, MRSA was confined to hospitals, with the first reports of community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA), sometimes called community-associated MRSA, surfacing in 1993 in a high school wrestling team. Its community prevalence has continued to grow, and recent statistics suggest that 50% of skin infections are now caused by MRSA.

Studies show that approximately 25% to 30% of the population is colonized, but not infected, with MRSA. That means nearly 1 in 3 people will come into contact with MRSA, including athletes involved in team or contact sports.

Who is most at risk?

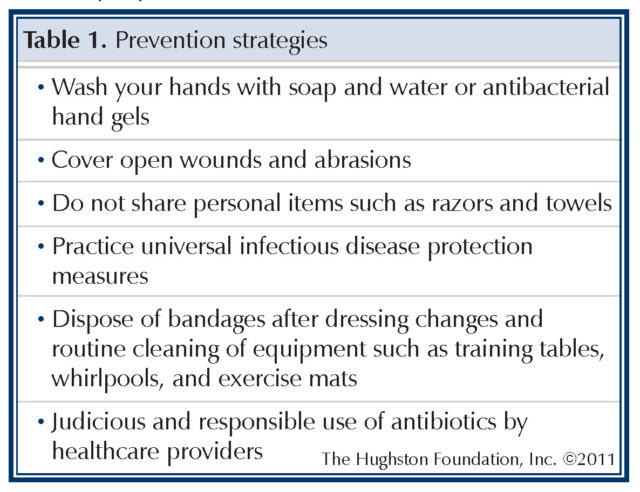

Athletes who are involved in high physical-contact sports, such as wrestling, football, and rugby are at risk of getting and spreading the infection. However, CA-MRSA infections have been reported among athletes in other sports such as soccer, basketball, field hockey, volleyball, rowing, martial arts, fencing, and baseball. Although little physical contact occurs in some sports during participation, skin contact or activities that lead to the spread of CA-MRSA skin infections can take place before or after participation, such as in locker rooms. Therefore, anyone participating in organized or recreational sports should know the signs of possible skin infections and follow prevention measures (Table 1).

When should you suspect CA-MRSA infection?

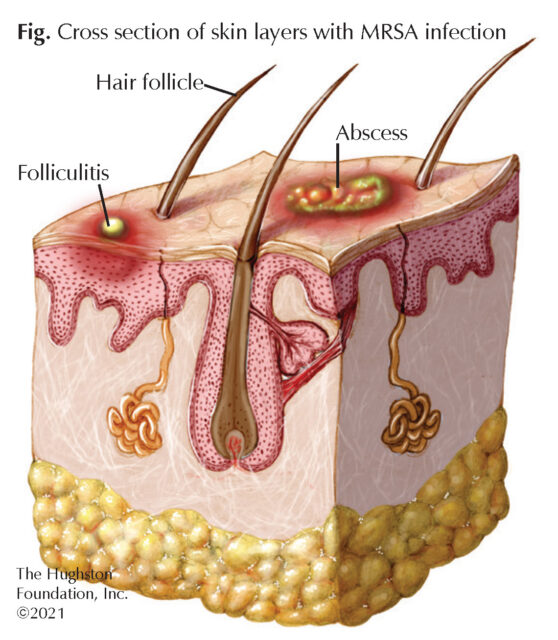

Most CA-MRSA infections appear as folliculitis (white headed pimples around hair follicles) or similar skin infection (Figure). The infection often begins with an infected pimple or insect bite. Some infections can progress to abscess formation, and though it is rare, it can persist to a life-threatening illness, such as rapidly progressing sepsis or pneumonia. The most common route of transmission is through an open wound, such as a superficial abrasion after contact with a MRSA carrier. The risk of transmission in athletes increases with poor hand washing, not showering after a workout, sharing personal items, such as razors, towels, and clothing, or not properly cleaning and disinfecting exercise or training equipment.

How is CA-MRSA treated?

The primary treatment for CA-MRSA skin and soft tissue infection includes incision and drainage if an abscess is present, followed by treatment with antibiotics. If caught early, incision and drainage is not always necessary. Your physician can culture any purulent material (pus) from the infected area and send it for a sensitivity profile to determine the most effective antibiotic.

Return to play

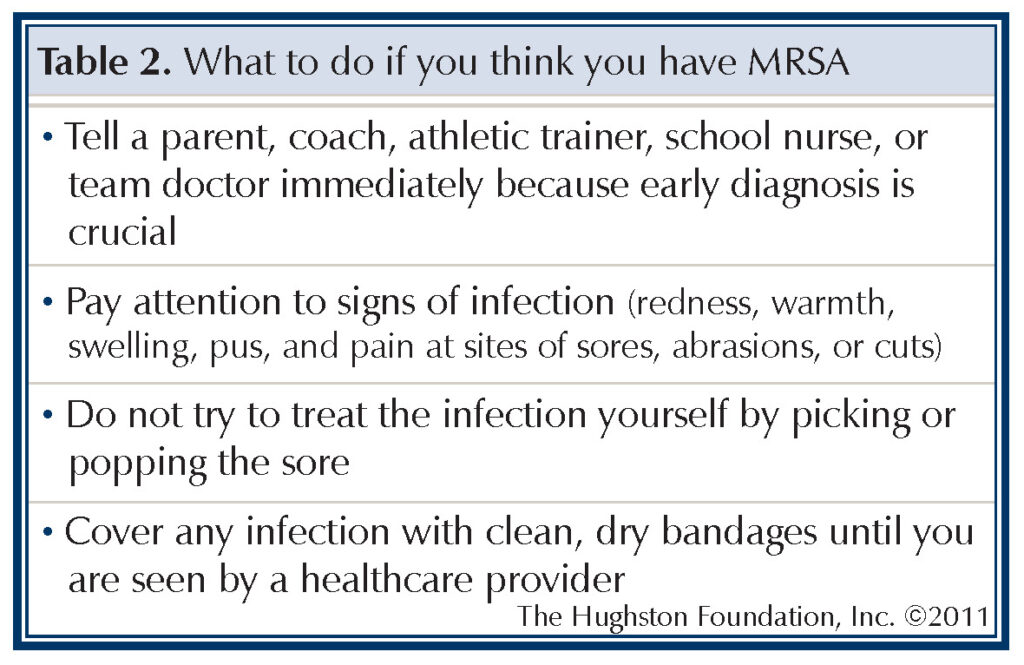

Athletes with mild cases of MRSA infection can return to athletic participation once an appropriate antibiotic treatment has begun and the risk of transmission to other athletes has been significantly reduced or eliminated. Cover abrasions or affected areas with protective clothing, and examine the wound daily for signs of recurrence or worsening of the infection. Warn athletes and teammates not to share personal items, and the training staff should disinfect equipment and surfaces that the infected athlete may have come in contact with (Table 2).

As with most medical conditions, certain measures can be taken to decrease the risk of developing and spreading MRSA. Everyone must have a heightened sense of awareness that CA-MRSA not only exists, but also is common. Measures must be taken to prevent spreading the bacteria and causing infection.

Author: John Akins, MD | Columbus, GA

Last edited on November 9, 2021