Researchers directly link obesity to earlier-age onset osteoarthritis, which may explain why obese patients tend to require total hip replacement on average 10 years earlier than non-obese individuals do. Total hip arthroplasty (THA or total hip replacement) in obese patients also poses unique challenges for surgeons. These patients often require more preoperative optimization, longer surgical time, and they tend to have a higher risk of complications, such as, infections, wound healing, and revision surgery. Despite the surgery being technically more difficult and with higher risks, functional outcomes for obese patients are comparable with patients who are at a non-obese weight.

Calculating obesity

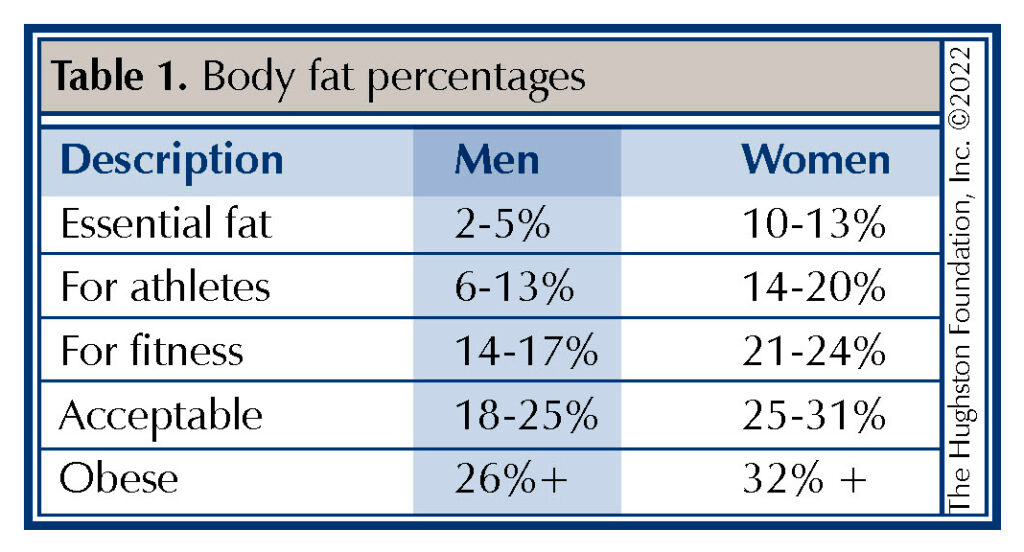

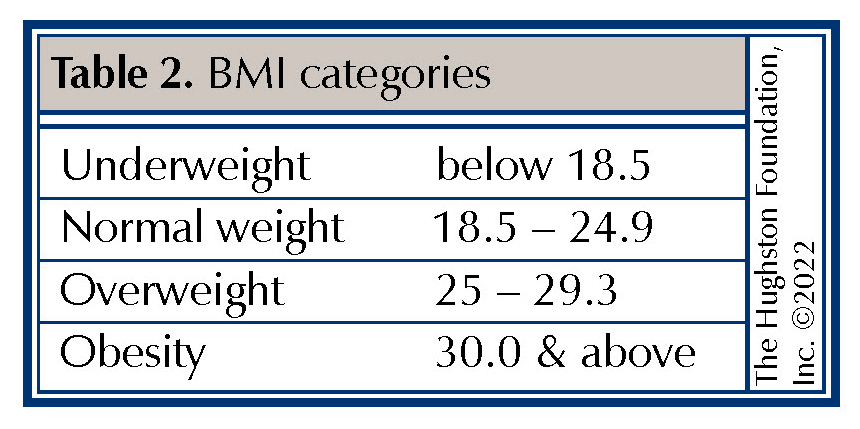

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a measure of the body’s fat content (Table 1.) based upon height and weight that applies to both adult men and women. Obesity levels can be determined from the BMI calculations (Table 2.). In addition to BMI, fat distribution can be measured using waist circumference (more than 35 inches in women and 40 inches in men) and waist-hip ratio.1 These measuring techniques can help give a more accurate description of different types of obesities, such as abdominal or central obesity (fat stored around the waist) or peripheral obesity (fat stored around the hip and thigh area). BMI classification have established underweight below 18; normal ranges as 18-25; overweight 25-30; obese 30-35, and morbid obesity >35.

Clinical studies have shown that there are higher complications rates in obese patients undergoing hip replacements. Comparing outcomes of obese patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty or a knee replacement, there were more complications in the hip surgery groups with higher rates of wound complications and reoperation rates.1 Hip surgery on obese patients can make every phase of the operation more difficult with respect to time and complexity. Their increased tissue mass can make exposure more difficult due to soft tissue limiting motion and the ability to manipulate the joint. This commonly presents issues with joint exposure and proper positioning of the hip replacement components.

Preparing for surgery

Working with obese and morbidly obese patients preoperatively is important to try to prepare them for surgery, optimize their risk, and set them up for a successful outcome. Any amount of weight loss prior to surgery can be helpful to lower their risk of an infection or other complications. For morbidly obese patients, this often involves a preoperative weight loss plan that includes healthcare providers in different fields, such as dieticians, primary care physicians, and sometimes, bariatric surgeons. Working with a physical therapist is also beneficial in the morbidly obese patient. Physical therapy can help strengthen surrounding hip and core muscles, provide gait training with assistance devices such as walkers or canes, and teach tips for seemingly simple activities that can be difficult after surgery, such as putting socks on or getting dressed. Furthermore, a discussion with your surgeon to decide on the best surgical approach for hip replacement for different types of obesity (i.e., central vs peripheral) is important. A patient’s height and weight may be important clinical factors that can influence the best surgical approach to hip arthroplasty as well.

Posterior surgical approach

The posterior method is the most commonly used hip approach for primary and revision hip replacement because it offers excellent exposure of the joint and can more easily be converted if a problem were to arise such as an intraoperative fracture of the pelvis or femur. The excellent exposure comes from the surgical release of the thick posterior hip joint capsule and adjacent external rotator muscles on the posterior aspect of the hip capsule. The surgeon must repair the muscles at the conclusion of the surgery.

Lateral and anterolateral surgical approaches

The lateral and anterolateral surgical approaches also release muscles in order to expose the hip joint. The gluteus minimus and medius (hip abductor) muscles are released during exposure and repaired at the conclusion as well. This approach has less risk of postoperative hip dislocation compared to the more commonly use posterior approach, but the violation of these hip abductors muscles (moves the leg away from the midline) can potentially lead to a postoperative limp.

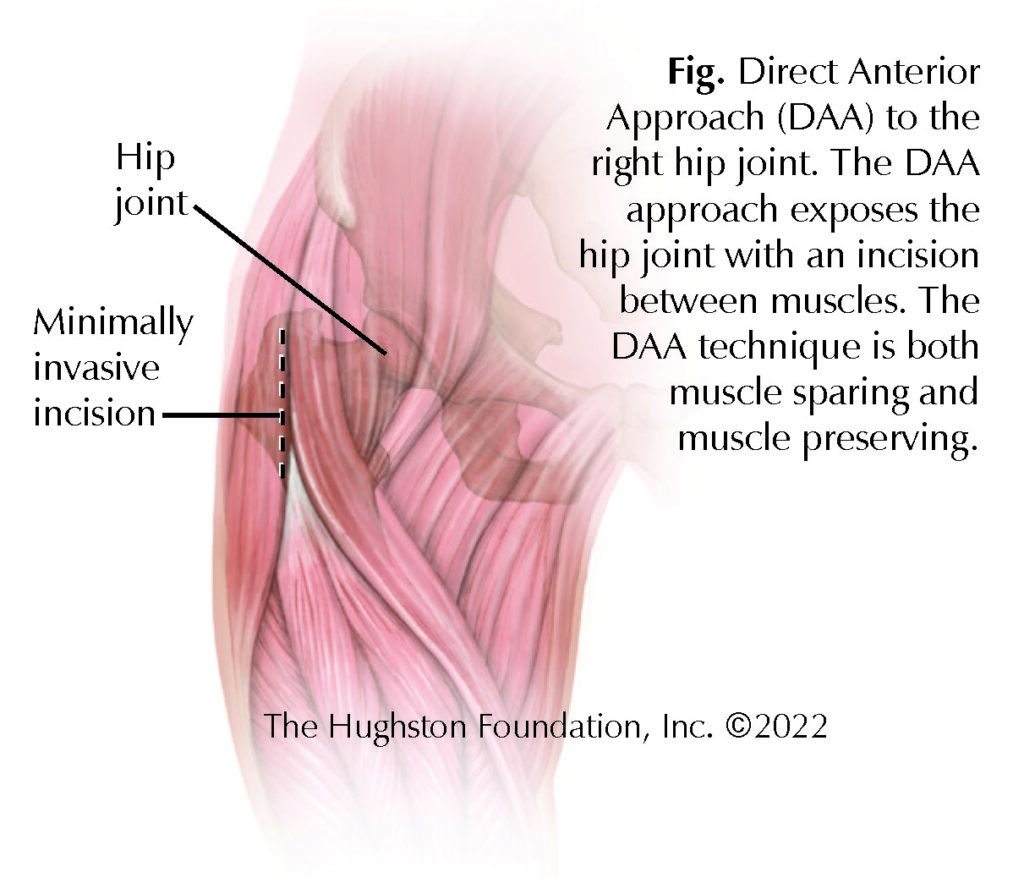

Direct anterior surgical approach

The direct anterior approach (DAA) is a technique used in hip replacement surgery that is muscle sparing (Fig.). This means that the exposure follows natural tissue planes to the hip, moving muscles rather than cutting through them.2 Since the direct anterior approach does not require the release of muscles to expose the hip joint, it means that surgeons do not have to make repairs to any muscles once the operation is complete.

Choosing a good surgical team

No matter what surgical approach you and your surgeon decide upon, either way, there is no short cut to a better quality of life. While all surgeries have inherent risks of complications, hip replacement as a whole, independent of the approach, has one of the highest satisfaction rates in all of orthopedic surgery. The most important factor is not the surgical approach, but the experience and reputation of your surgeon. An experienced doctor will ensure all modifiable risk factors are optimized prior to surgery so that each patient has the best chance for success.

Author: Michael Saint-Jean, BS, MS-II, and Reily Cannon, BS, OMS-II | Columbus, Georgia, and Henderson, Nevada

References

- DeMik DE, Bedard NA, Dowdle SB, et al. Complications and Obesity in Arthroplasty-A Hip is Not a Knee. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3281-3287. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.02.073

- de Steiger RN, Lorimer M, Solomon M. What is the learning curve for the anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty? Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 2015;473(12):3860-3866. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4565-6

Last edited on March 9, 2023