Stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, is a condition that causes the tendons (connects muscle to bone) in your hand to click when you bend your finger or thumb. In severe cases, the tendon becomes trapped and locks your finger in place.

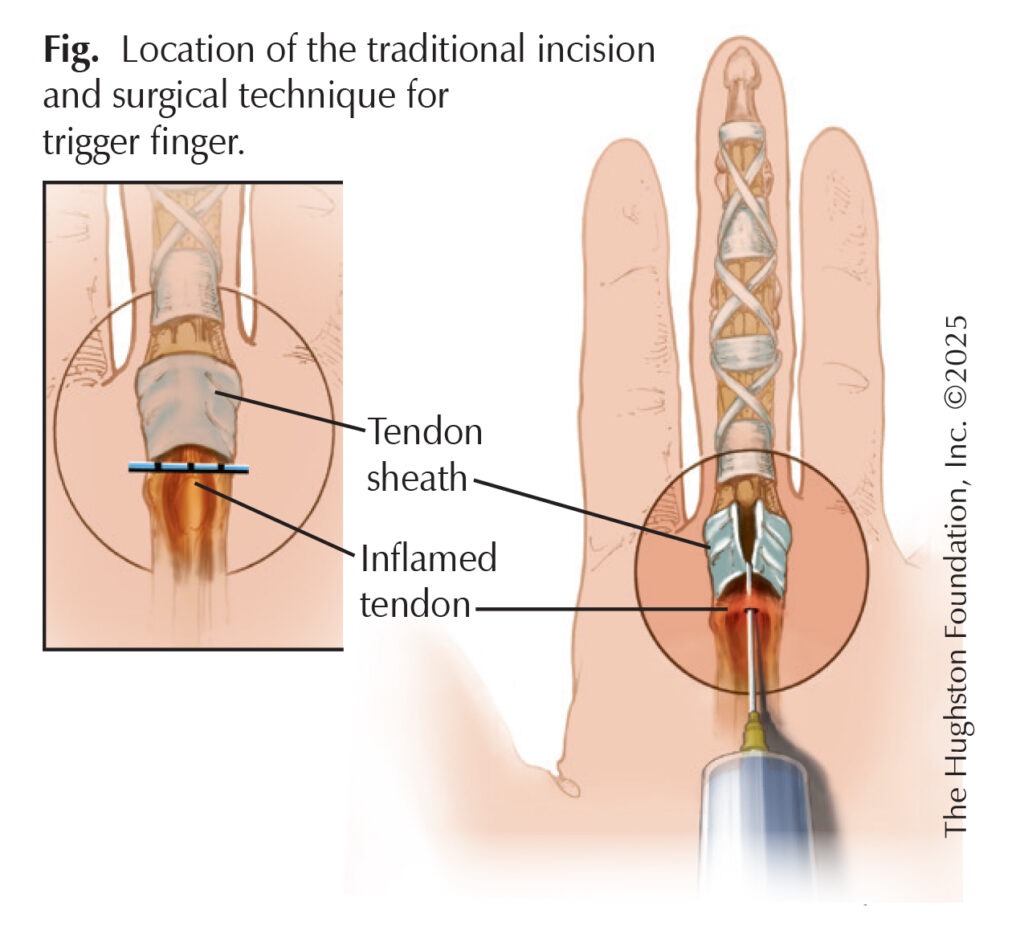

In the hand, there are flexor and extensor tendons that connect to muscles in the forearms. Flexor tendons are on the palm side of the hand and when their attached muscles contract, they allow you to curl your fingers inward as if you were making a fist. These tendons are covered with a protective sheath that attaches at the ends of the bones in the fingers and thumbs. Multiple ligaments (tissue that connects bones to bones) hold the tendon and sheath down towards the bone. The tendon sheath produces a small amount of fluid, which allows it to glide during times of flexion (bending) and extension (straightening). The tendon sheath can become inflamed and swollen which prevents the tendon from sliding smoothly and can cause the finger to catch and lock in a bent position causing pain and impairment.

Risk factors

Trigger finger is about 6 times more common in women than in men. It has its highest incidence in adults 40 to 60 years of age; and, interestingly enough, it can occur in children less than 8 years old. For children, the condition is usually painless and resolves on its own. Trigger finger happens to roughly 2% of the population and around 20% of patients with diabetes¹. Other conditions like chronic inflammation from rheumatoid arthritis or patients with carpal tunnel syndrome can develop trigger finger as well. Patients with Dupuytren’s contractures (fibrosis of the hand’s connective tissue) tend to develop trigger finger at higher rates as well.

Symptoms

The symptoms of trigger finger develop gradually, usually without any underlying evidence of a preceding injury. Pain in the finger along the base with movement or applied pressure is an early symptom of the disease. After a while, you may develop a lump that can be palpated (felt) during a physical exam. The finger can become stuck in the flexed position and during times of extension, you can hear an audible click. The release of the bump past the ligament can cause significant pain. Symptoms are usually worse in the morning or after extended periods of rest. As the day goes on and you use your hand more, you often experience improvement in movement. The ring finger and thumb are the most common fingers affected.

Diagnosis

An orthopaedist can diagnosis the disorder in the office after a physical exam. During your exam, the doctor may try to extend the fingers to check for stiffness and catching of the tendon while also noting any tenderness. Your physician may not order imaging since x-rays will not show anything significant. While MRI (magnetic resonance imaging shows the bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments) could show a swollen tendon, it can be an unnecessary expense.

Nonsurgical treatment

Your doctor will start with conservative methods first. This involves resting your hand, which helps decrease the swelling within the tendon. Exercises to help with stiffness and the range of motion of the fingers can decrease or alleviate symptoms. Patients can also wear a splint to help prevent the finger from bending. If no improvement occurs, the doctor can prescribe medication in the form of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, to help with the inflammation. Injections of steroids into the base of the tendon where it catches can help to resolve the condition with a 90% success rate.1 The steroids help in the form of reducing inflammation. Steroid shots can be less effective in patients with diabetes, especially since the steroid can cause the blood sugar to rise.

Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment

If the injections stop providing relief or if the finger locks into the flexed position, your doctor may recommend surgery. The procedure involves a small incision at the base of the affected finger. The surgeon can cut the sheath so that the tendon can glide freely once again. Surgeons perform the surgery as an outpatient procedure and recovery usually takes 2 weeks. Some patients with jobs that require frequent strenuous use of their hands can take a month to recover; however, full recovery with no symptoms of swelling or stiffness takes about 3 months postsurgery.

Author: Tristan L. Melton, BSA | Columbus, Georgia

Reference

- Blood TD, et al. Tenosynovitis of the hand and wrist: A critical analysis review. JBJS Rev. 2016;4(3):e7.

Last edited on October 17, 2025