There is a good chance that you or someone you know has experienced an injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). ACL tears represent more than 50% of knee injuries and affect more than 200,000 people in the US each year, with direct and indirect costs greater than $7 billion annually.¹ The ACL is the most commonly torn ligament of the knee and has been responsible for many career-ending injuries for athletes.² Amateur and professional athletes dread the thought of experiencing this injury. However, improved research in treatment and advanced surgical techniques have made it possible to treat the injury effectively with both operative and nonoperative management.

Anatomy of the knee

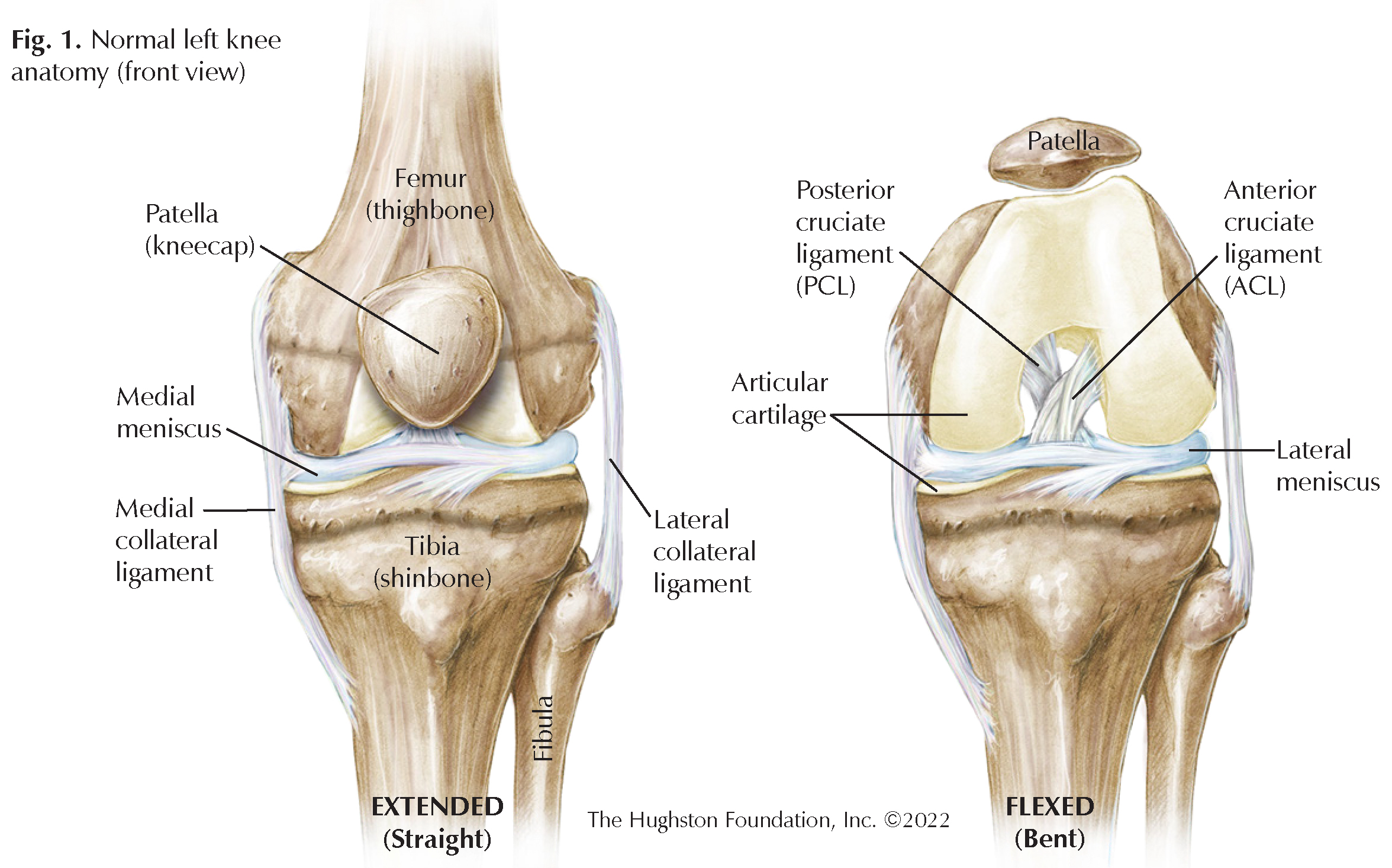

To understand ACL injuries, we must first understand the anatomy of the knee and the function of the ACL in stabilizing the knee (Fig. 1). One of the largest joints in the body, the knee region is where the femur (thighbone) and the tibia (shinbone) meet. Covering the ends of these bones is articular cartilage that protects the bones from rubbing together while bending the knee. Crescent shaped disks of fibrocartilage—the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus—are also in between these 2 bones and function as shock absorbers during activities such as standing, running, and jumping. The patella (kneecap) sits on top of the joint and slides through a groove in the femur.

For the knee to bend, the bones must be attached in a dynamic, yet stable fashion. This is where ligaments are useful. A ligament is tough connective tissue that connects 2 bones to each other and allows structural support while maintaining slight elasticity for movement. The knee joint has 4 main stabilizing ligaments: anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL), and lateral collateral ligament (LCL). They all function in opposing ways to stabilize the knee throughout flexion (bending) and extension (straightening) of the joint. The ACL and PCL make a crisscross pattern and together they keep the knee joint stable during back and forth movement. The ACL keeps the tibia from slipping too far in front of the femur. Although ligaments, cartilage, and tendons (tissue that connects muscle to bone) provide great stability to the knee joint, they also allow tremendous power transfer through the leg for physical activity.

Injury

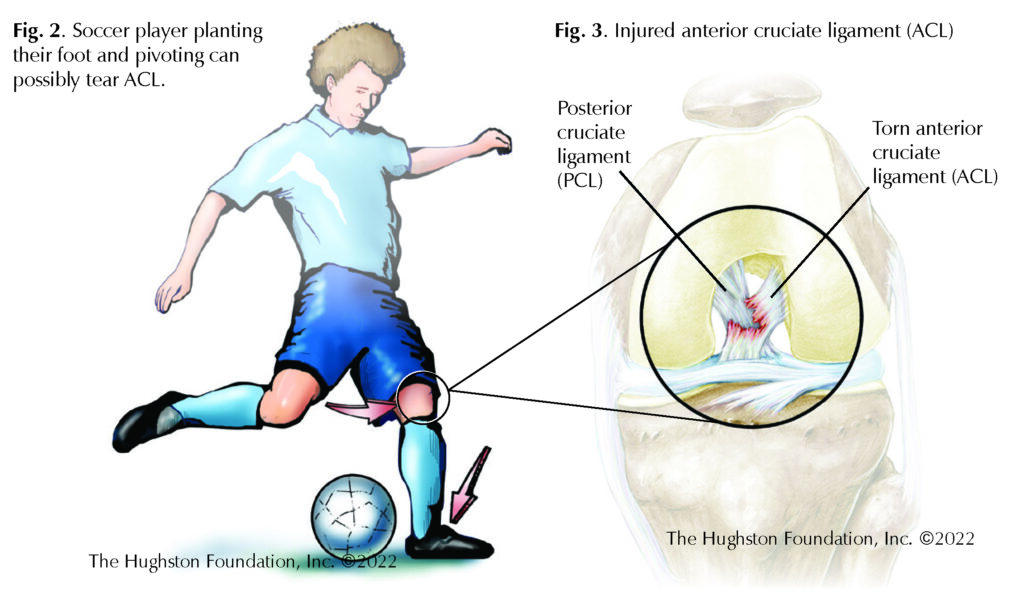

Most ACL injuries occur as a low velocity, noncontact injury, such as during a decelerating and pivoting motion. For example, this can happen when a soccer player is running in one direction, plants his or her foot, and quickly reverses direction to cut back across the field. The foot and lower leg remain still while the upper body turns with the knee in a flexed position (Fig 2). Athletes who experience ACL injuries usually describe a popping sound or sensation just prior to the onset of symptoms. While some patients experience minimal or no pain, most experience excruciating pain deep inside the knee joint with a feeling of instability, particularly when the knee is in full extension (Fig 3). Pain followed by significant swelling and stiffness typically occurs during the next 24 hours.

ACL injury is best evaluated immediately after injury. If you have an athletic trainer or sports medicine physician nearby, you may notice them maneuvering the knee to test the integrity of the ligaments and cartilage of the knee. Trained medical professionals can assess the injury from the physical exam, but doctors often use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, a test that shows the bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments) to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the extent of the injury.

Who is at risk for injury?

Adolescents aged 16 to 18 years old and particularly those who participate in more vigorous intensity sports with little down time³ are at the highest risk for injury. Females are 3 times as likely to experience an ACL tear as their male counterparts.4 When considering specific sports, females are at a greater risk playing soccer, while males are at a greater risk playing football.¹

Treatment options

There are both operative and nonoperative methods to treating ACL injuries. Athletes who want to return to a high level of competition are ideal surgical candidates. Often, patients worry that an ACL tear must be repaired immediately to avoid future complications. Data on the timing of surgery does not indicate that immediate repair is superior to delayed repair. Since it is not imperative to go to surgery urgently, the physician may recommend a trial of nonoperative treatment with close follow-up for 3 months. If there is no improvement after 3 to 6 months, surgery may be an option.

Nonoperative treatment

An orthopaedic surgeon considers nonoperative treatment for patients with a low activity demand and no significant instability. Nonoperative treatment typically involves a combination of physical therapy, bracing, and lifestyle modifications. The physician will continue to evaluate the injury every few weeks to ensure progress is being made. Emergence of symptoms such as the knee “buckling” or “giving way” signifies instability. At any time nonoperative management fails, surgery is often recommended to prevent further injury to the knee.

Operative treatment

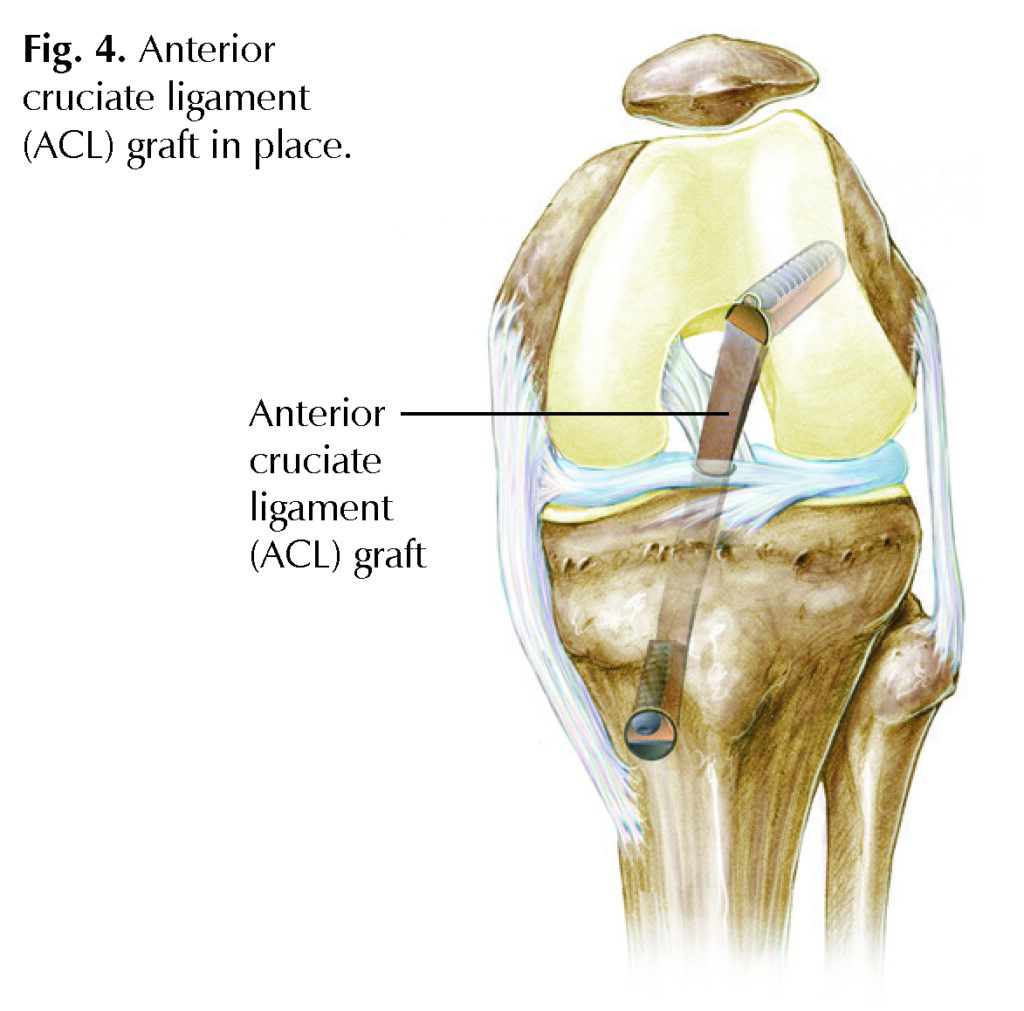

ACL reconstruction surgery is typically an outpatient procedure, which means you will arrive at the hospital, have the procedure, and go home on the same day. Once the torn ACL is removed, a “new” ACL, called a graft, will be inserted in its place (Fig 4.). A graft can come from the patient (an autograft) using the hamstring tendon, patellar tendon, or quadriceps tendon, or from an organ donor, which is called an allograft. Once the new ACL graft is in position and the remaining structures evaluated, the incision is closed, and the patient is taken to the recovery room.

After surgery

Patients are placed in a hinged brace following surgery and will progressively weight bear on the knee over the next 6 weeks. During the first 6 weeks, physical therapists direct rehabilitation exercises with a focus on pain and swelling control, patellar mobilization, and quadriceps muscle activation. During weeks 6 to 12, the therapist will focus more on strengthening the leg muscles and increasing stability and endurance. Often, the goal for returning to sport is a minimum of 6 months, but the timeline varies between athletes.

Returning to the playing field

ACL injuries can be a scary and painful experience for many athletes, but current surgical procedures have been successful in returning many to the playing field. If you have experienced an ACL injury and want to return to a high activity level, a tendon graft is a reliable way to restore knee stability. Be sure to express your desired activity level when discussing treatment options with an orthopedic surgeon who is experienced in ACL reconstruction.

Author: Christopher Rogers, BS | Columbus, Georgia

References

- Musahl V, Karlsson J. Anterior cruciate ligament tear. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2341-48.

- Mall NA, Chalmers PN, Moric M, et al. Incidence and trends of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2363-70.

- Musahl V, Burnham J, Lian J, et al. High-grade rotatory knee laxity may be predictable in ACL injuries. Knee Surg, Sports Traumatol, Arthrosc. 2018;26(12):3762-69.

- Bohy Y, Klouche S, Herman S, et al. Professional athletes are not at a higher risk of infections after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Incidence of septic arthritis, additional costs, and clinical outcomes from the French prospective anterior cruciate ligament study (FAST) cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(1):104-11.

Last edited on May 11, 2022