Once rare, injuries to the chest muscles, particularly the pectoralis major muscle, are becoming more common. In fact, a recent study noted that of the 365 cases of pectoralis major ruptures reported in the medical literature from 1822 to 2010, 76% occurred over the past 20 years.¹ Pectoralis major injuries can range from contusions (bruises) and inflammation to complete tears and frequently result in pain, weakness, deformity in the contour of the chest, and, ultimately, a decline in overall shoulder function. These injuries most often occur in active individuals who participate in sports or perform heavy labor and can be the result of either an acute traumatic event or chronic overuse. Pectoralis major tears are common in younger males who lift weights² and in older athletes who do not warm-up adequately; however, these kinds of tears have even been reported in the elderly.³ When pectoralis major injuries occur, they can be disabling, especially to athletes.

The chest muscles

The chest muscles

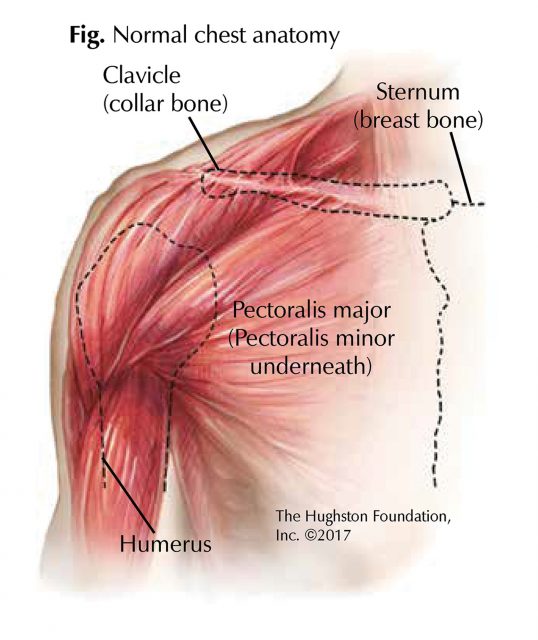

The 2 pectoralis muscles, the pectoralis major and the pectoralis minor (the larger and smaller muscles of the chest) connect the front of the chest wall with the humerus (upper arm bone) and shoulder (Fig). The pectoralis major is a thick, fan-shaped muscle consisting of 2 heads or portions, the clavicular and the sternal. The clavicular head originates from the anterior border of the medial half of the clavicle (collar bone) while the sternal head arises from the sternum (breast bone) and first through sixth ribs. The 2 portions of the muscle then converge on the outer side of the chest with the subclavius muscle (the small, triangular muscle between the clavicle and first rib) to form the axilla or armpit. The multiple origins and insertions of the pectoralis major muscle allow it to initiate a wide range of actions on the arm, enabling it to adduct (draw toward the body), flex (bend), extend (straighten), and internally rotate (turn toward the body).

Causes

Over time, repetitive or prolonged activity may cause the tendons of the pectoralis major muscle to degenerate, resulting in a strain. Chronic muscle imbalances, weaknesses, tightness, and abnormal biomechanics, especially when combined with excessive training, can also contribute to the development of a pectoral strain. By contrast, acute strains or tears to the pectoralis muscle happen when a force goes through the muscle and tendon that is greater than they can withstand. This can occur while weight training, especially when performing a bench press, chest press, or pectoral fly, and is more likely to happen when using free weights than machines. For example, if too great an external force is applied when the muscle is at its maximal stretch point, as during the downward movement of a bench press, it will rupture at the tendon juncture. When this occurs patients typically report a sharp pain with a pop.

Classification

Tears to the pectoralis major muscle may be small and partial or may constitute a complete rupture. Additionally, they can be classified as 1 of 3 grades, based on the number of muscle fibers torn and how much function has been lost, with grade 3 representing the most extensive damage. The majority of tears are grade 2.

Symptoms

Following a pectoralis major tear, the patient may have bruising, swelling, and deformity of the chest and upper arm. In addition, he or she may report pain and loss of strength when pushing with the extremity. The pain is localized to the chest and front of the shoulder or armpit, but may radiate into the upper arm or neck and may increase from an ache to a sharper pain with activity.

Diagnosis and assessment

In the acute phase of injury, a physical exam may be difficult to perform because swelling from the injury can distort the shoulder and pain can affect strength and motion testing. Once the swelling has resolved, the contour of the chest and shoulder may appear abnormal. The strength of the muscle can be tested by having the patient adduct while internally rotating (moving toward the body) the arm and adding resistance (pulling away from the body). The results can then be compared with results from the opposite arm.

Imaging is used to differentiate a pectoralis injury from other types of disorders and to determine its extent. X-rays should be taken to look for a possible bone fragment on the tendon or other associated fracture or dislocation. CT (computed tomography) can be used to evaluate fractures identified on x-rays for surgical fixation. Ultrasound is an inexpensive modality that can be used to assess the presence of a tear or retraction of the tendon while an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can be performed to determine the site and extent of injury.

Treatment

The treatment for a pectoralis major injury depends upon the severity of the injury, the extent of muscle function, and the patient’s health and general activity level. Nonsurgical treatment must be considered in patients who have low demand, are elderly, or have either partial tears or tears in the muscle belly. Initial management with immobilization, rest, and cold therapy followed by strengthening and stretching can offer a satisfactory to excellent functional result. Shoulder motion returns and patients can resume daily activities.4 In those patients who either need to return to full strength and function or are concerned with cosmetic appearance, surgical repair is recommended. In a recent study, patients were highly satisfied with surgical repair of the pectoralis major, reporting a return of strength, structure, and overall function.5 The need for rehabilitation after surgery varies depending on how the muscle was repaired. In general, patients can return to normal activities 4 to 6 months after their procedure.

Outcomes

The management of pectoralis major injuries is patient specific. In sedentary or low-demand individuals with partial or complete tears, nonsurgical management can provide acceptable to excellent results. In those who demand function and form, surgical treatment may be the best option. While complications such as failure of repair, infection, and stiffness can occur, they are fairly rare. Generally, full return to activity and improved appearance can be expected following surgical repair and rehabilitation.

Author: Dan Morris, DO | Columbus, Georgia

References:

1. El Maraghy AW, Devereaux MW. A systematic review and comprehensive classification of pectoralis major tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:412-22.

2. Bak K, Cameron EA, Henderson IJ. Rupture of the pectoralis major: a meta-analysis of 112 cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(2):113-9.

3. Beloosesky Y, Hendel D, Weiss A, et al. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle in nursing home residents. Am J Med. 2001;111(3):233-5.

4. Rijnberg WJ, van Linge B. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle in body-builders. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1993;112(2):104-5.

5. Mooers BR, Westermann RW, Wolf BR. Outcomes following suture anchor repair of pectoralis major tears: a case series and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2015;35:8-12.

Last edited on October 19, 2021