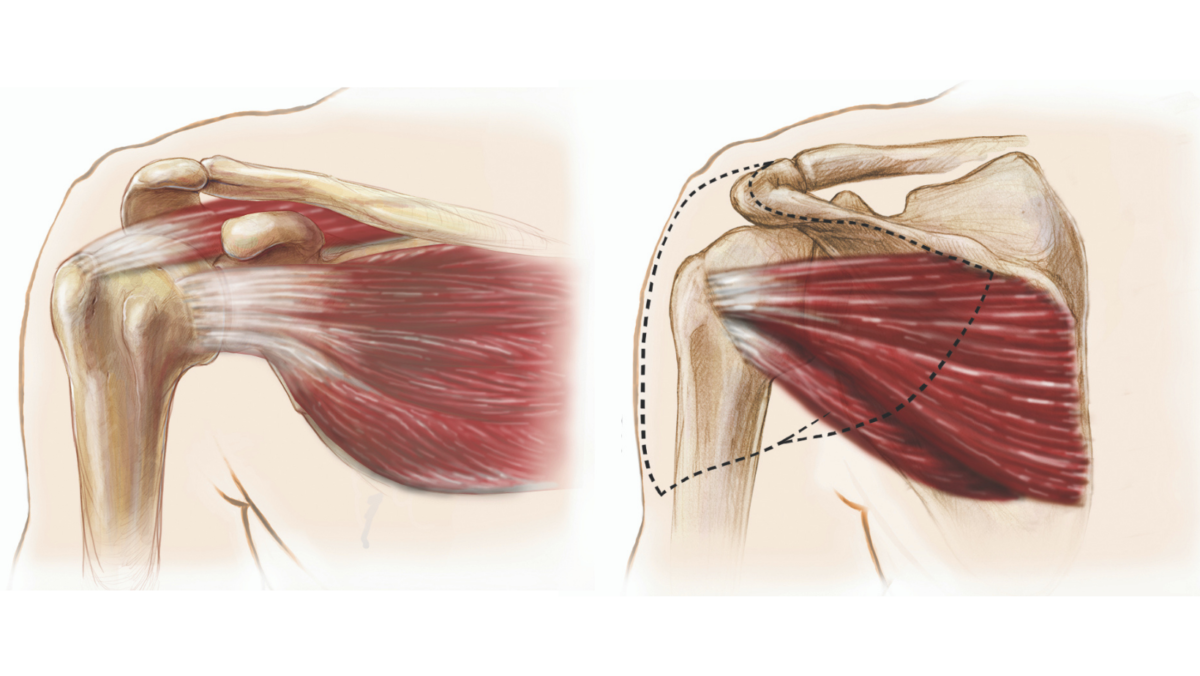

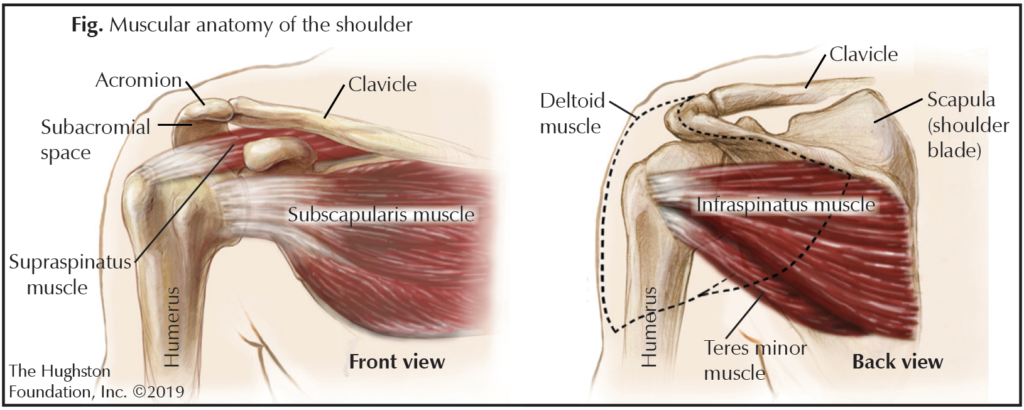

The rotator cuff is a group of muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis) and tendons (tissue connecting muscle to bone) that surrounds the shoulder joint. This group of muscles provides stabilization while also allowing movement, which is why the shoulder is one of the most flexible joints in the body. Interestingly enough, many patients with rotator cuff tears have no symptoms at all, while others complain of pain and weakness in the shoulder. A rotator cuff tear can range from small to large in size, it can be a partial tear in 1 of the muscles, or it can be a partial or complete tear of a tendon. Almost 1 out of 3 people over the age of 60, and 2 out of 3 people over the age of 70 have full thickness rotator cuff tears. Depending on the severity of the tear, there are various treatment options, which include nonoperative management and shoulder arthroscopic surgery.

What causes a tear?

The rotator cuff can become injured in a number of ways. Most commonly, the tear is due to chronic muscle and tendon degeneration that comes with aging. Additionally, they often occur in conjunction with a shoulder dislocation in patients over 40 years old. You can injure your rotator cuff by falling on an outstretched arm or develop an injury over time doing repetitive activities at work or while playing a sport. Another possible mechanism is from impingement (weakening and tearing at the tendons) of the rotator cuff on the acromion (the bone right above the shoulder joint). The acromion process can develop bone spurs that can rub on the rotator cuff tendons, causing impingement.

Risk factors

There are several risk factors associated with rotator cuff tears, but advanced age is one of the most significant. Others include having a rotator cuff tear on the other shoulder, smoking, family history, poor posture, high cholesterol, history of trauma, and occupations demanding heavy labor and repetitive movement.

Seeking medical advice

When to seek medical advice can be a difficult question to answer since patients have a wide range of how much pain and dysfunction they can stand before it triggers a visit to the doctor’s office. Where some patients develop a small discomfort in their shoulder and immediately see their doctor, others wait until their pain is unbearable and they have lost most of the function in their shoulder. Certainly, any amount of pain and discomfort, weakness, and loss of shoulder function should warrant a visit to a sports medicine or shoulder-trained orthopedic physician.

Screening and diagnosis

Your physician will examine the shoulder, moving it through various positions and maneuvers in an attempt to localize the problem. Radiographs or x-rays, will also be obtained to evaluate for any bony involvement. Depending on the length of time the problem has been going on, or if there has been a recent traumatic injury, the physician may decide to order magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, a scan that shows the bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments) of the shoulder. Additionally, your physician may also decide to perform an injection into the subacromial space (the space between the rotator cuff muscles and the acromion). This is not only a treatment option, but it can also provide the physician with valuable information regarding your diagnosis by whether you experience pain relief or not.

Treatment

Most rotator cuff tears can be initially managed with nonoperative treatment. These include physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, and subacromial corticosteroid injections. It is important to consider patient expectations and symptom severity when deciding on nonoperative treatment as this is different for every patient.

If the injury is severe or an acute tear following some sort of traumatic episode, such as a fall or shoulder dislocation, or if nonoperative management is not working, the physician may recommend surgery. Surgery is performed arthroscopically (using a small camera to look inside the shoulder joint). This is typically done using 3 or 4 small incisions around the shoulder. The surgeon will examine the shoulder anatomy and clean up any loose and frayed tissue, remove any bone spurs, and then repair the tear depending on the appearance of the rotator cuff and the size of the tear.

The surgery usually takes an hour to an hour and a half depending on what needs to be done. After surgery, your shoulder will be placed in an abduction shoulder brace (a sling that holds the arm out to the side) and you will be given specific instructions that help the healing process and encourage a positive outcome.

Postoperative rehabilitation

Postoperative protocols for rehabilitation vary by physician; however, most exercise treatments follow the same general principles. Initially the shoulder is kept immobilized. Then a period of passive range of motion exercises follows, which mean that your arm is moved without you exerting any effort. Then active range of motion begins, which will progress to a resistance-training program.

Outcomes and complications

A rotator cuff repair can offer predictable success with a long track record of pain relief and patient satisfaction. Medical literature shows excellent outcomes in patients with partial and full thickness tears.

Failure to heal is the most common cause of a failed rotator cuff repair. Patients at risk for failure include those who are 65 years of age and older, smokers, diabetics, and those who have large size tears, muscle atrophy (shrinking), and those who do not follow the surgeon’s postoperative rehabilitation plan. More rare complications include injury to nerves in the shoulder, infection, and stiffness. Often, postoperative stiffness can be managed with physical therapy.

Don’t shoulder the pain alone

Rotator cuff tears are common in the aging population and can debilitate patients with extreme pain and functional limitations. For most circumstances, conservative treatment should be attempted first as many patients will respond positively. Surgical treatment has shown to have excellent results and should be weighed between the patient’s pain and function, as well as avoiding progression of the tear. If you have shoulder pain, see an orthopedist who specializes in the shoulder. A speciality-trained shoulder physician will quickly and accurately diagnose your problems and get you on the road to recovery.

Author: Roman I. Ashmyan, DO | Columbus, Georgia

Last edited on April 27, 2022