A hot topic in sports medicine today concerns the presence of sickle cell in athletes. Nationally publicized occurrences of sports injury and deaths related to sickle cell have spawned both interest in and debate on what to do about the condition. Last year, the NCAA implemented mandatory screening for sickle cell trait among all Division I athletes starting with the 2010-2011 academic year.

What is sickle cell?

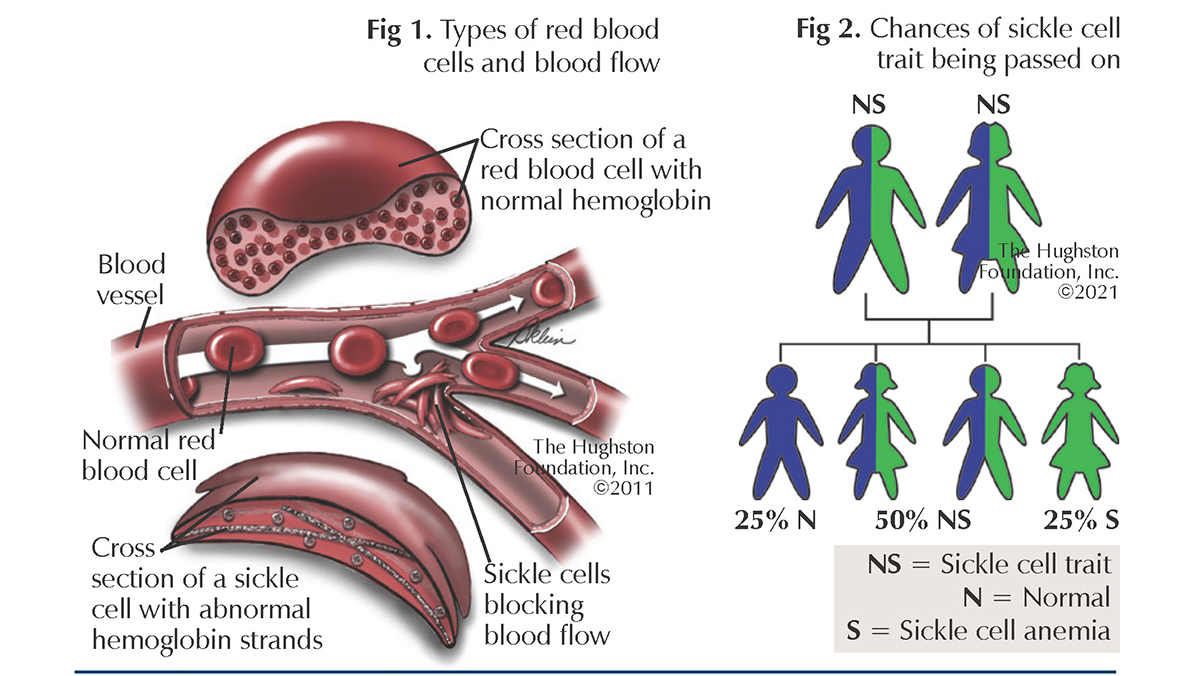

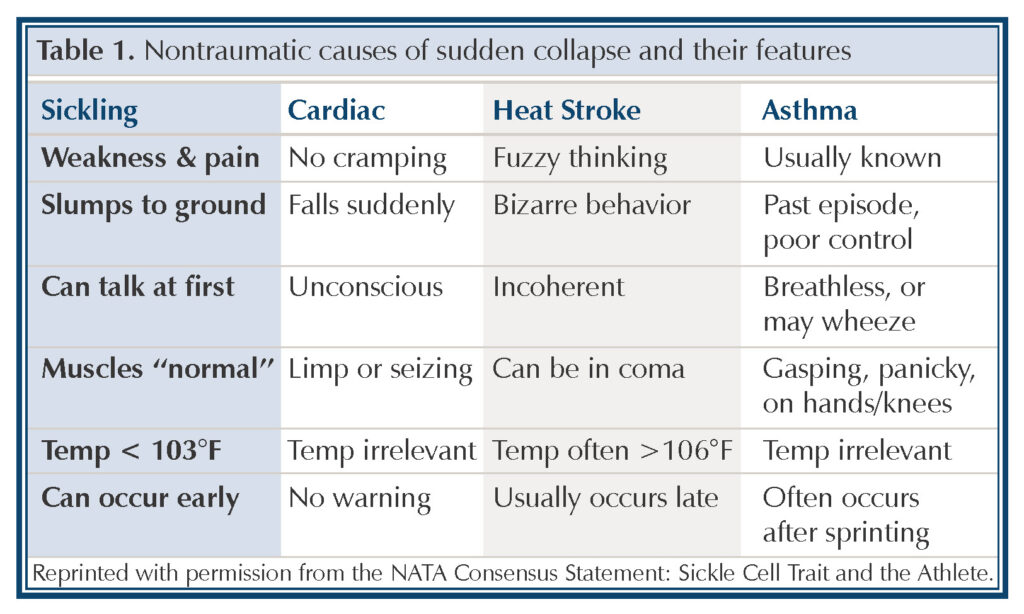

Normal hemoglobin are round in shape and carry oxygen in our blood cells. Crescent, or sickle shaped, hemoglobin cannot adequately bind and carry oxygen. The shape also causes the cell to move more slowly through blood vessels and when multiple sickled cells clump together, they can clog or impede blood flow (Fig. 1). This occurrence, called sickling, or sickle crisis, can be associated with severe pain. Sickle cell trait is present in an individual who has 1 normal gene for hemoglobin (Hb) and 1 gene for sickle hemoglobin (HbS). Sickle cell trait is different from sickle cell anemia, in which individuals have 2 genes for HbS (Fig. 2).

Who has sickle cell trait?

Sickle cell trait is a common and usually benign condition found in more than 3 million Americans. The sickle gene, HbS can be found in Americans with African, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, Indian, Caribbean, and South and Central American ancestry; therefore, testing newborns at birth is required in all states. Some non-life-threatening complications of sickle cell trait are splenic infarction (death of tissue in the spleen) and gross hematuria (blood in the urine). Most people with sickle cell trait live normal healthy lives; however, in athletes who have sickle cell trait, some specific and possibly dangerous clinical problems can occur.

The most serious concern for an athlete is exertional sickling which can quickly progress to exertional rhabdomyolysis (ER). ER is an underreported and misdiagnosed sudden collapse syndrome that can be fatal. Exertional sickling occurs during extremely strenuous exercise, such as that seen in preseason athletic conditioning. Since the year 2000, there have been 16 nontraumatic sports deaths in NCAA Division I football. Four were cardiac related, 1 due to asthma, 1 from exertional heat stroke, and 10 from complications of exertional sickling. That’s 63% of the deaths, which makes exertional sickling the leading cause of death in NCAA Division I football.

How does it happen?

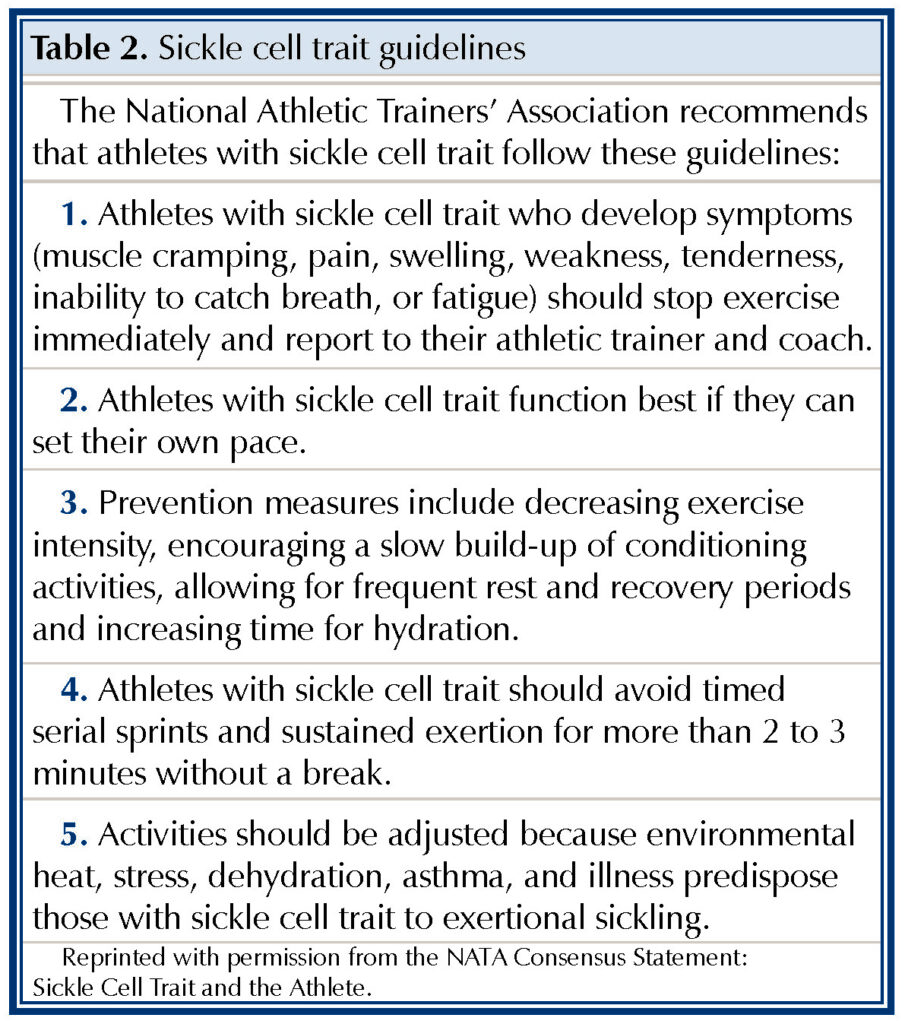

Nontraumatic, sudden collapse during sporting activity in an otherwise healthy individual can be attributed to cardiac (heart) problems, exertional heat stroke, asthma, or sickling. Unfortunately, sickling presents differently among individuals and can be mistaken for heat stroke or sudden cardiac collapse. If misdiagnosed, the appropriate treatment can be delayed, resulting in more serious and often fatal outcomes.

Exertional sickling is directly related to intensity of exercise and can begin within 2 to 5 minutes of intense, sustained exercise without rest. The high intensity causes a cascade of symptoms: hypoxemia (low oxygen), acidosis (increased acid content in blood), hyperthermia (elevated temperature) and cell dehydration which together lead to sickling. Because intensity is the cause, the deaths associated with sickle cell trait have occurred during conditioning for the game, not while practicing or playing.

Prevention

The best offense is a good defense, so we start with prevention. The best method of prevention is early recognition of the condition (Table 1). The sports community needs to recognize those who are at risk for exertional sickling and be vigilantly alert to the initial signs and symptoms that indicate trouble. Professional athletes and NCAA athletes are now routinely screened for sickle cell trait so that team coaches, trainers, and physicians will know who is at risk. Again, exertional sickling is an intensity-related syndrome seen during conditioning-type activities that involve an all-out exertion by an athlete. Therefore, all who are involved with a player’s training need to know who and what to look for to help the athlete safely participate in his or her sport (Table 2).

Author: Jaclyn Jones, DO | Columbus, Georgia

Last edited on November 9, 2021