According to the CDC, plantar fasciitis affects about 10% of the population, making it the most common cause of heel pain. Runners, military recruits, and people who stand for most of the workday often experience plantar fasciitis. Additionally, young male athletes, middle-aged females, and obese individuals are at risk. The classic telltale sign is pain with the first step of the morning. Then it improves during the day, but often returns by the end of the day. Based on the signs and symptoms and who experiences the heel pain, plantar fasciitis is also called jogger’s, tennis, or policeman’s heel; heel spur syndrome; and the medical term, calcaneal periostitis is used to described the chronic condition.

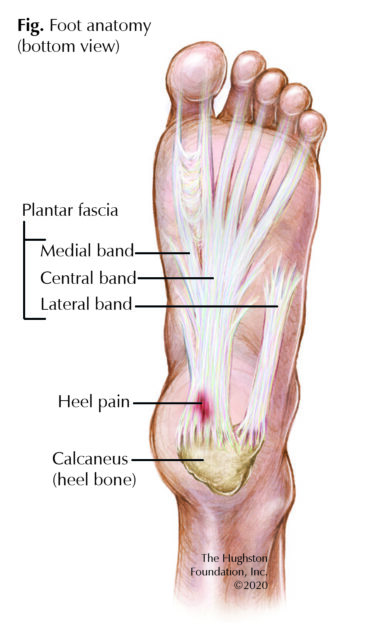

Foot anatomy

Foot anatomy

A long ligament of 3 bands (medial, central, and lateral), this connective tissue originates at the medial aspect of the calcaneus, or heel bone, and extends all the way across the bottom of the foot to the toes (Fig.). Overall, the function of the plantar fascia is to provide tension and support to the arch of the foot as well as aid in shock absorption while walking. The central band is the thickest and strongest part of the plantar fascia and it is the most involved segment in plantar fasciitis.

Signs and symptoms

Patients often experience pain along the inside, or medial side of the heel, which is most severe with the first steps after a period of inactivity. The pain tends to decrease in intensity as the activity level increases throughout the day, but becomes more severe by the end of the day, which explains why active people experience greater pain after exercise rather than during activity. Almost a third of the time, plantar fasciitis affects both feet and it sometimes involves the entire foot including the toes. While the symptoms associated with plantar fasciitis often resolve with a good outcome, it can take 6 to 18 months, and sometimes longer, for patients to experience relief. Thus, seek early diagnosis and treatment for heel pain, especially if you are at risk for plantar fasciitis.

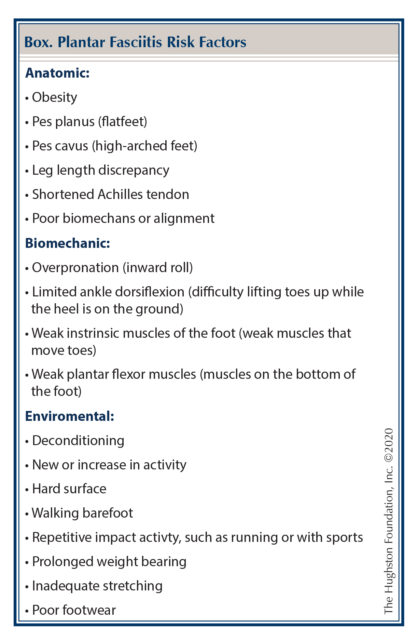

Risk factors

Risk factors

The most common cause of plantar fasciitis is repetitive stressing of the plantar fascia, which results in microtears and a vicious cycle of recurrent inflammation. At one time, physicians thought bone spurs were responsible for the microtears in the ligament; however now, most researchers do not believe that is the case. Many risk factors are associated with developing plantar fasciitis, such as obesity, prolonged standing or inactivity, flatfeet, and poor footwear (Box). Consequently, regular exercise, walking, and losing weight can lower your risk or help relieve your symptoms.

Diagnosis

To identify your heel pain, your doctor will perform a thorough physical exam of your foot and ankle. The first physical notation is your arch type, since a high arch is a major risk factor. Your doctor will also press on the plantar fascia while you move your foot to see if you experience more or less pain with movement. For example, your pain may get worse when you flex your foot while the doctor is pressing the plantar fascia, but it may improve while you point your toes down. Your doctor may also have you stand with your feet flat on the floor and raise your toes to see if it increases or decreases your pain.

Often, your doctor will order x-rays of your foot to rule out a fracture. While laboratory tests are not needed to make a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis, advanced forms of imaging, such as ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, a scan that shows the bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments) can be used if you do not experience relief after 6 to 8 months of nonsurgical management.

Treatment

Your options include both nonsurgical and surgical interventions, but up to 90% of patients experience relief with nonsurgical modalities. Your doctor can recommend over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin and ibuprofen first or you may need a prescription for a stronger dosage. If pharmacologic therapies do not help improve your symptoms, a corticosteroid injection into the plantar fascia area of the foot may be helpful. Additional modalities include splinting your foot while you sleep, wearing over-the-counter or custom-molded shoe inserts during the day, stabilizing your foot with a cast or walking boot, and completing a physical therapy regimen. Physical therapy options range from at-home exercise routines to formal therapy with modalities that include icing, taping, ultrasound therapy, or deep massage.

If you are among the 10% of patients whose symptoms do not resolve after 6 to 12 months of nonsurgical treatment, then your doctor may suggest a surgical procedure to release the plantar fascia. Overall, the procedure has a 70% to 90% success rate. Complications associated with surgery of the plantar fascia include injury to nerves and blood vessels, instability of the arch of the foot, and overloading of the outside, or lateral aspect of the foot.

A step forward

Plantar fasciitis is a debilitating disease, which can limit your daily functions and activities. The pain caused by plantar fasciitis is often self-limiting, which is why you should seek medical attention early for an appropriate diagnosis and treatment plan. If you are experiencing chronic heel pain, talk to your doctor, getting help is the first step toward a pain-free life.

Author: Mudassar Khan, DO | Columbus, Georgia

Last edited on July 27, 2022