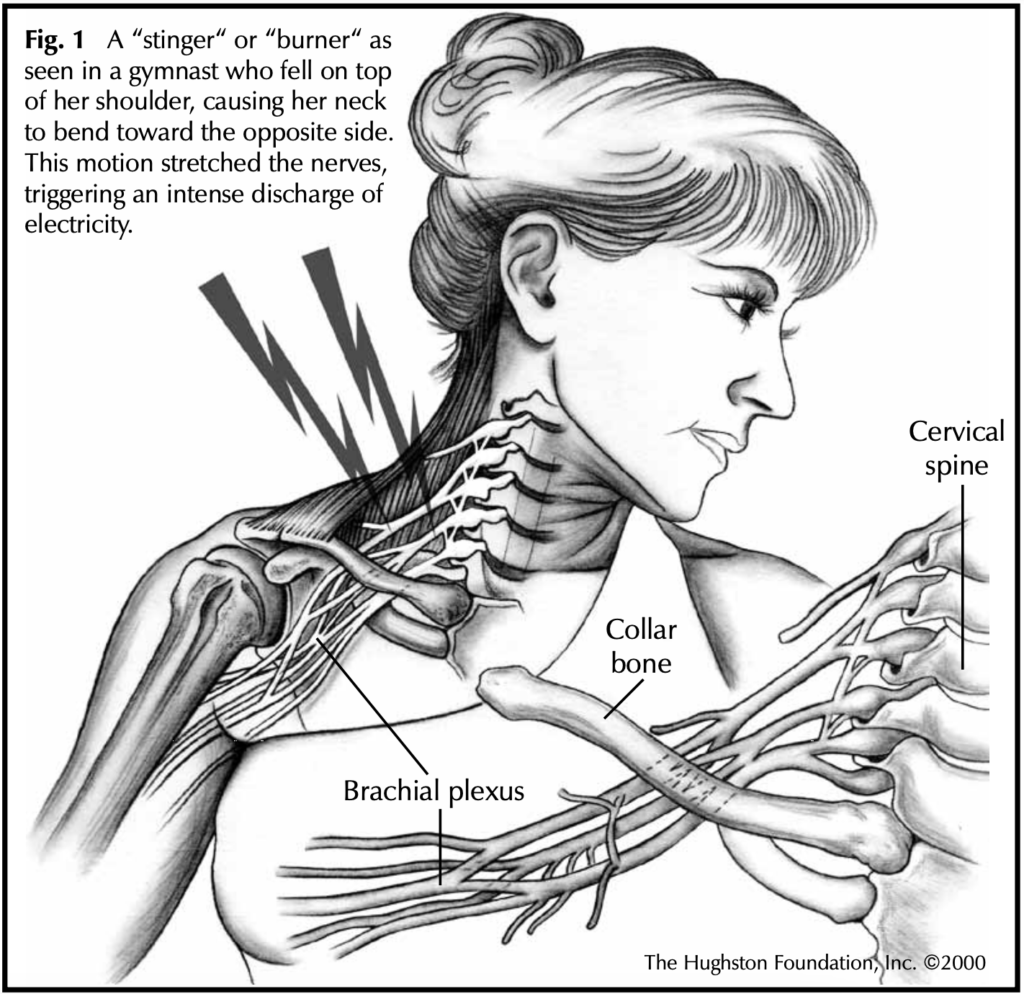

Few sports injuries are as eyeopening for the athlete as a “stinger” or “burner.” This intense neurologic (nerve) event occurs most commonly in football players. It also can occur in people who participate in wrestling, cycling, gymnastics (Fig. 1), snow skiing, martial arts (Fig. 2), or other sports. This article discusses the condition in football players and highlights several key points.

What is a stinger or burner?

A stinger or burner is an intensely painful nerve injury. The nerves that give feeling to the arms and hands originate from the cervical (neck) spinal cord. As these nerves leave the neck, they form the brachial plexus (see Fig. 1). They weave together then branch as they pass under the clavicle (collar bone) on the way to the shoulder.

Nerve injury often happens when the athlete makes a hard hit using his shoulder. The direct blow to the top of the shoulder drives it down and causes the neck to bend toward the opposite side. This motion severely stretches or compresses the nerves and triggers an intense discharge of electricity. For a few seconds, the electricity shoots down the nerves to the tip of the fingers.

After this intense electrical discharge, the nerves’ motor fibers that allow movement in the arm do not function well. The dysfunction is evident by weakness in the arm. The weakness often involves the muscles that allow the athlete to lift the arm away from the body, to bend the elbow, and to grip. Symptoms also include sensations of tingling and of burning or stinging pain in the arm and hand. The extent of the damage varies considerably. The pain usually lasts only a few minutes, but the weakness can last weeks, months, or years. Rarely, the injury may cause permanent damage.

Treatment of a stinger or burner usually begins as soon as the player runs off the field with the limp arm hanging by his side. The certified athletic trainer, physical therapist, or team doctor carefully examines the cervical spine, evaluates nerve function in the neck and upper back, tests muscle strength, and tests reflexes. If the athletic trainer, physical therapist, or doctor suspects that the athlete has a spinal cord injury, he or she treats the condition as a medical emergency with full spinal precautions.

How do I know it’s a stinger and not something else?

Stingers or burners produce symptoms in only one arm. Injuries that can accompany a stinger include fractures, dislocations, or damage to the ligaments (tissue connecting two bones) of the cervical spine. Therefore, when treating an athlete who has a stinger, the doctor takes appropriate precautions to protect the spine.

A spinal cord injury usually causes symptoms involving more than just one arm and possibly the legs. This injury must be treated as a medical emergency. A contusion (bruise) to the spinal cord in the neck during athletic competition can lead to temporary quadriparesis, producing symptoms of pain and tingling in both arms and both legs. Certain athletes may be more prone to this injury because the space in their necks through which the spinal cord travels is narrow (see “Congenital Spinal Stenosis,” p. 3). Other injuries to the spinal cord can cause lasting, serious nerve damage. The health care provider always treats neck injuries with full precautions until serious injuries are ruled out.

When can the injured athlete go back in the game?

When can the injured athlete go back in the game?

If the certified athletic trainer, physical therapist, or team doctor determines that the athlete’s sense of feeling, strength, neck motion, and reflexes have returned to normal, the athlete may be able to return to the game. All protective gear should be inspected to ensure it fits properly and is in good condition. Additional shoulder pads or a neck roll may be added. Do not attach restraining straps or other similar devises to the helmet because they can lead to more severe injuries. The athlete should be examined frequently during the game for further problems including recurrence of symptoms.

How should the athlete be treated following the game?

After the game, the athlete should be re-examined in the locker room and, if necessary, at his doctor’s office. An athlete who has a stiff neck following a stinger is more prone to further, more serious injury and needs a thorough evaluation of the neck, shoulder, and nerves by an orthopaedic doctor. An athlete who has had a stinger cannot return to play until the health care provider notes that he has no pain or tenderness and that he exhibits full range of motion and strength in the neck, shoulder, and arm.

How do we prevent these injuries?

Preventing recurrent stingers is important. Subsequent injuries tend to be increasingly severe and can damage the nerve permanently. Athletes, coaches, officials, athletic trainers, and parents need to ensure that athletes follow these three minimal guidelines. First, use proper technique in tackling as mandated by the 1979 football rule outlawing spearing or head tackling. Second, make sure that the shoulder pads and neck roll, if used, fit properly and are in good condition. Third, before the season begins, participate in an exercise program to develop full range of motion and protective strength of the neck and shoulder muscles.

Author: Kurt E. Jacobson, M.D. | Columbus, Georgia

Last edited on October 18, 2021