The shoulders produce 90% of the driving force that propels the body through water, which explains why the most common musculoskeletal complaint in swimmers is shoulder pain. The term “swimmer’s shoulder” includes a number of painful overuse injuries that often correlates with a sudden increase in training or using poor swimming techniques. Because there are various parts of your shoulder in action during the swimming stroke, you may injure and experience pain at any single or multiple sites about the shoulder. Pain can be the result of 1 or more conditions, such as reduced shoulder stability, muscle or tendon (tissue connecting muscle to bone) strains, nerve irritation, or sprains from stretching or tearing ligaments (tissues connecting bones).

Anatomy

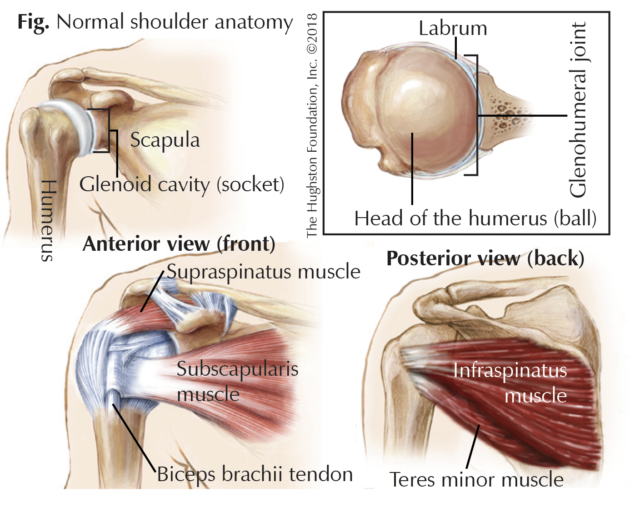

The glenohumeral joint, or shoulder, is a ball-and-socket joint formed by the head (ball) of the humerus, or upper arm bone, with the glenoid cavity (socket) of the scapula (shoulder blade). The shoulder cavity is shallow, which reduces the amount of contact between the bones. This provides increased freedom of motion at the expense of stability. However, the glenoid labrum, a ring of cartilaginous fiber that lines its circumference, deepens the cavity by about 50%, allowing for more surface contact, a better fit, and added stability. In addition, the joint capsule and its ligaments (tissues that connect bone to bone) provide some added stability. The glenohumeral joint is also known as a muscle-dependent joint. It is primarily stabilized by the biceps brachii, or muscle on the anterior (front) side of the upper arm, and the tendons of what are called the rotator cuff muscles. The rotator cuff is made up of 4 muscles, which work together, to help keep your shoulder centered in the socket during motion. These include the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles. Each of these muscles originates from the scapula and has a tendon that attaches to the head of the humerus (Fig).

Diagnosis

Identifying the source of pain in swimmer’s shoulder is crucial to obtaining the correct diagnosis and best treatment. Your physician will look for the characteristics of your discomfort, such as the location, radiation, timing, and position of pain, as well as the type of swimming stroke used and if you have had any changes in training. Additionally, a thorough health history is essential when identifying the source of shoulder pain. Your physician may order x-rays to rule out any abnormal anatomy and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan) to evaluate the shoulder’s muscles, tendons, and ligaments. If your physician suspects neuropathy (nerve damage), an electromyography (EMG) test that measures the muscle response to a nerve’s stimulation may be ordered as well.

Treatment

In general, nonoperative treatment is the primary approach to swimmer’s shoulder. Rest and icing the injury and taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, such as aspirin or ibuprofen are the initial recommended management techniques. You should rest your shoulder and stop the movement or activity that caused or reproduces your shoulder pain. Apply ice for 20 to 30 minutes every 2 to 4 hours to help reduce the swelling. It may be difficult for you to lift your arm or to sleep; therefore, you may need to wear a sling or have your shoulder taped for support and you may need to sleep in an upright position or use a pillow for added support. Once you have passed the acute phase of inflammation, you should consider modifying your training regime so that it does not aggravate the injury and cause additional pain.

Depending on the severity of your injury, your physician may recommend a corticosteroid injection into the shoulder that helps to reduce swelling and leads to pain relief. Each patient reacts differently, however the injection can relieve the pain and swelling for weeks or months or alleviate the problem altogether.

Another nonsurgical option is a physical therapy program that focuses on both stretching and strengthening exercises to neutralize any uneven muscle strength. During swim training, a muscle strength imbalance and muscle shortening can occur in the shoulder. Strengthening exercises are used to re-establish a muscular strength balance allowing a more synchronized movement of the shoulder. When performing stretches, the athlete must be mindful to include both anterior (front) and posterior (back) aspect of the shoulder as to not create an imbalance that may exacerbate some injuries. Once you have improved motion and muscle coordination, you can begin a gradual return to training.

When nonoperative treatment fails or if your physician has identified a structural problem, you may need surgical treatment. The type of structural problem present will direct surgery. Common injuries that require surgery in swimmers are multidirectional instability, impingement syndrome, and labral tears. For multidirectional instability, the surgeon tightens the soft tissue structures to increase stability of the joint. However, this procedure can decrease motion in the shoulder and may affect athletic performance afterwards. For athletes that fail therapy or injections for subacromial impingement, surgical treatment with removal of inflamed bursal tissue is an option. The recovery is relatively quick as there is no down time for healing of tissue. In those with a labral tear that have failed conservative treatment either labral repair or debridement can be performed. Returning to swimming after surgery varies according to the procedure preformed. The goals and expectations of the athlete should be examined and considered in relation to expectations after surgery.

Dive in

Of all the joints in the body, the anatomy of the shoulder allows for the greatest range of motion. The demands you place on your shoulders during swimming, coupled with the anatomy can lead to a wide range of injuries. If you experience shoulder pain, stop what you are doing and evaluate your technique and posture. Once you give the shoulder a short rest, restart your training slowly so you do not re-injure the joint. If the pain returns, it may be time for you to have the injury evaluated by a physician. After taking a detailed history and physical exam, your doctor can make an accurate diagnosis and start you on a treatment plan. The correct diagnosis will help guide appropriate treatment and ultimately a successful return to sport.

Author: Daniel J. Morris, DO | Jasper, Alabama

Vol. 30, Number 3, Summer 2018

Last edited on October 18, 2021